Using external events to inform marketing decisions is nothing new. Business decisions are often made based on outside influences believed to impact sales. For instance, well-known retailer Walmart has been basing its marketing strategies on the correlation between weather conditions and sales of particular products for years — even without fully understanding the rationale behind these inferred weather-related purchases. But using correlation to try to understand how a particular event, such as weather or an ad campaign, impacts sales can lead to serious business mistakes.

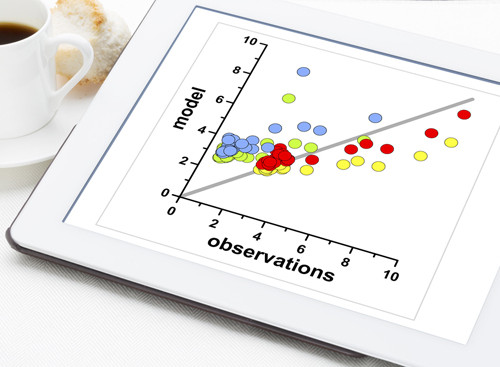

To understand the pitfalls, let’s begin by defining what correlation actually means. Correlation is a statistical measurement indicating the scale and direction of a relationship between at least two variables. These variables are not necessarily related, and a change in one variable does not necessarily affect the others. In other words, correlation is often nothing more than simple coincidence.

For example, a supermarket may notice that it sells more ice cream on a sunny day, and then use that information to predict store sales. While it may be human nature to want to draw a connection (when it’s warm out, more people want to eat ice cream), creating such an artificial cause and effect relationship can be misleading. For instance, it may be a bank holiday weekend, or the launch of a new ice cream flavour, that’s driving an increase in sales.

In fact, shoppers may avoid the supermarket on sunny days altogether – preferring to be outside in the sunshine – so ice cream sales could actually be lower than they would have been if it had been a cloudy day.

So, if brands shouldn’t base their marketing strategies on correlation, what’s the alternative? Causality is proven cause and effect, meaning an event can be shown to be the direct result of one or more other events. Imagine, for example, an insurance provider that notices it receives a large number of policy subscriptions when it rains, and comes to the conclusion that it can look at weather patterns to anticipate sales. But what if this data happened to be collected during an unseasonably rainy period, and the real reason behind the increase in sales was people actually needing the insurance services they offer? By uncovering actual cause-and-effect relationships, causality enables marketers to understand what’s really driving conversions and revenue, and make better decisions as a result.

While confusion between correlation and causality is widespread throughout the advertising industry, nowhere is it more prevalent than with TV data. Many marketing measurement solutions take attributed digital data and overlay it with aggregated TV Gross Rating Point (GRP) data. At first glance, this may seem to provide valuable insights, but when the principles of correlation vs. causality are applied, it becomes evident this technique is flawed. Correlating aggregate TV data with digital touch point data dilutes the accuracy of attributed data and only provides insight into a potential correlation. While it may reveal some interesting patterns, the resulting correlations are not substantial enough to use as a basis for marketing decisions.

Generating insights that can intelligently inform marketing strategies and tactics requires an understanding of causality not correlation. And to understand causality, it is essential to consider all of the marketing touch points experienced by a consumer, across every marketing channel. Only this type of “full picture” view can isolate causation from correlation, providing brands with the ability to understand the true cause of a conversion and optimise their marketing efforts based on this understanding. Robust marketing attribution solutions provide such a full picture view, consolidating market data from online and offline channels and quantifying the impact that every channel, campaign and tactic has on overall marketing success.

Drawing a connection between outside events and sales may be entertaining, and correlations between the weather and conversions can produce thought-provoking patterns. But to avoid costly business mistakes, marketers need to stop saving for a rainy day and optimise their strategies using causation, not correlation.